Category: News

-

Dandenong bus service needs recognised in award ceremony

The need for better seven-day buses in Greater Dandenong was recognised at the Public Transport Users Association Annual General Meeting, held in Melbourne on Thursday November 14. The association’s annual Paul Mees Award for public transport advocacy went to Peter Parker and the FixDandyBuses campaign. This campaign succeeded in gaining government funding for an upgraded…

-

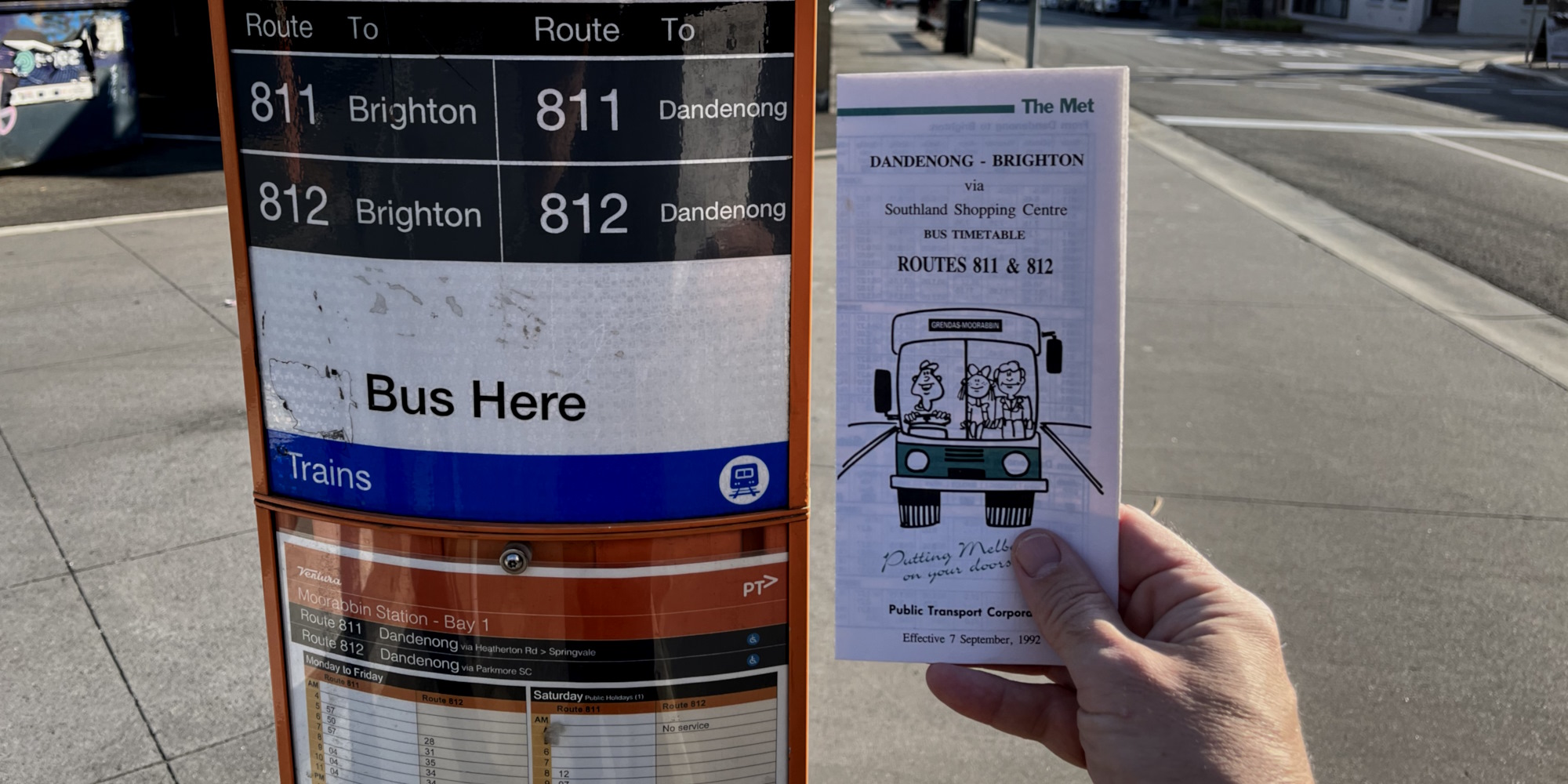

Call for heritage listing for Melbourne’s public transport timetables

PTUA calls for heritage listing for Melbourne’s public transport timetables

-

V/Line: coming fare cuts set to worsen crowding

Service upgrades, including full length trains, are needed to cope with crowding.

-

Limos to fix station car park pain

The PTUA has welcomed a new government plan to provide access to public transport by hiring limousines to collect passengers from home to get them to their local station. With some car parks costing more than $100,000 per space, taking train users to the station by limousine has been found to be cost-competitive with the…

-

New logos on the way, as PTV and Vicroads merge

The PTUA has uncovered Department of Transport (DOT) plans to further integrate public transport and road operations, following the integration of Vicroads and Public Transport Victoria into the one broader organisation in 2019 [1]. The next stages of this integration are about to take effect, starting with the merger of the PTV and Vicroads brands…

-

Fares discussion welcome, but better service is still the main game

The Public Transport Users Association has welcomed the conversation on public transport fare reform sparked by the release of a new Infrastructure Victoria report “Fair Move: Better Public Transport Fares for Melbourne“. But PTUA President Dr Tony Morton said many of the proposed measures, like off-peak discounting, would only work properly in the context of…

-

COVID-19 smashes the life from cities, which is why we must smash COVID-19

by Tony Morton As COVID-19’s second waves wash over our technologically advanced civilisation, so follows the commentary on what this pandemic means for cities and for daily life in the future. Public transport sits at the heart of the discourse, and for good reason. In normal times, public transport sustains the life of the world’s…

-

Australia must ‘move on’ from freeway fantasy, not High Speed Rail

In response to the Grattan Institute’s calls for Australia to ‘move on’ from High Speed Rail, the Public Transport Users Association notes the limitations of their analysis, and calls for urban megaroads projects to receive the same level of scrutiny. Evidence has shown again and again that urban motorways induce more traffic, rather than “busting”…

-

Membership offer – Join PTUA for a year for the cost of a week of Myki

Swapped your Myki for video meetings? For the same cost as a week of Myki, you can join the PTUA for a year! Support the campaign for better public transport for just $45. Click here to join now PTUA regular annual membership is discounted to $45 for a year – the same as a weekly…

-

Infrastructure Victoria misses the bus on public transport pricing

A report on transport pricing by Infrastructure Victoria contains some potentially valuable suggestions on pricing of roads and parking, but is breathtakingly naive in its approach to public transport fares. As part of a comprehensive suite of measures to ‘rationalise’ the pricing of transport in Victoria, the IV report proposes scrapping the Myki zone system…

-

Myki Passes now able to be paused

Following our approach to the State Government, PTV have advised us today that they can now pause your Myki Pass. By pausing a Myki Pass, any remaining travel days will be ready for use when you are ready to get back onto public transport. This applies to both Commuter Club (through PTUA or other organisations)…

-

COVID-19

Please note that due to COVID-19 the PTUA is not running member meetings for the moment. There may also be a delay in processing paper membership forms and other correspondence, as our volunteers may not be attending the office during this period. Members wishing to renew are encouraged to do so online. Commuter Club /…