Much has been made in recent years of the ‘disruptive’ effect on urban transport of new ride-hailing services summoned by an app on your smartphone, operated by companies such as Uber and Lyft. Originally styled as ad-hoc taxi or ‘ride sharing’ platforms, their presence in US cities (especially) has grown to the point where they are now described in official documents as Transportation Network Companies or TNCs. The original companies have been joined by a plethora of start-up businesses, claiming not just to provide a superior user experience to taxis, but also to outdo the humble bus in efficiency and user convenience.

In cities like San Jose, and in suburban areas of large cities like New York, Boston, Austin and Los Angeles, these TNCs have persuaded local authorities to replace part or all of their traditional bus networks with subsidised Uber-style minivans that operate point-to-point in response to demand, rather than on fixed routes. ‘Microtransit’ is used as a generic term for this type of service to differentiate it from regular mass transit that has a fixed route and timetable.

On first impressions the idea sounds attractive. Who has not heard of suburbs in Melbourne where the buses all run mostly empty? Given the operating costs involved, isn’t it plausible that replacing the timetabled buses with a subsidised taxi service would not only save Victorians money but also be more convenient for passengers, since the service could run virtually door-to-door?

In April 2018 the agency Infrastructure Victoria, created by the Andrews Government to advise the state on transport and other infrastructure needs, embraced this view in its report Five Year Focus – Immediate Actions to Tackle Congestion. Among its recommendations is “replacing poor performing routes with low cost, customer-responsive services”. More specifically, to achieve this the government should “[i]ntroduce innovative public transport services such as on-demand bus and ride sharing”.

Responding to this advice, the Victorian Government has progressively been introducing pre-booked ‘FlexiRide’ bus services in some outer suburbs—initially as a replacement for the older ‘TeleBus’ service in the outer east, but increasingly in lieu of regular fixed-route buses in new growth suburbs such as Melton South and Tarneit North.

Despite its superficial attractiveness, in reality such ‘demand responsive’ service is likely to do the opposite of what’s claimed. Evidence suggests it’s likely to increase public transport subsidies, congestion and car dependence. Here’s why.

Microtransit: neither cheap nor convenient

The first problem with ‘on-demand’ microtransit is the same as with any attempt to design transport service primarily by reacting to demand rather than just ‘predicting and providing’ a uniform standard of service upfront (as is done with the road network). Any on-demand service will be inherently retractive because, unlike a regular turn-up-and-go service, potential passengers must expend effort to learn about its existence and the booking mechanism prior to travel, rather than just showing up at the bus stop. Should unexpected new demand appear, such services (being inherently small scale) are likely to be overwhelmed before they can scale up to cater for it, resulting in a poor experience for newcomers. All in all, when this kind of service is established in a car-dependent area, there is no reason at all for the area not to remain car-dependent.

The second problem is that the ‘flexibility’ of these routes is a double-edged sword. Providing a semblance of door-to-door service for more than one or two people at a time introduces ad-hoc detours that eat up travel time and undermine the service’s ability to compete with private car travel. If passengers can’t count on a reliable arrival time at their destination, they also can’t reliably connect to other public transport services such as regional trains that only run once an hour or less. This is another reason it is difficult for on-demand services to scale up easily if demand ever increases beyond a low level.

Of course, public transport itself solved this problem over a century ago (and some argue, as early as the 17th century thanks to mathematician Blaise Pascal no less) by operating fixed direct routes that put lots of origins and destinations within walking distance, rather than trying to run past everyone’s front door. Sure enough, as TNCs UberPool and Lyft Line scale up in the USA, they have found themselves doing the same thing, and becoming more and more like ordinary bus services. The more things change, the more they stay the same!

Melbourne’s own FlexiRide services also operate with fixed stop locations rather than door-to-door, and require at least one end of the journey to be at a designated ‘hub’ such as a railway station, shopping centre or school. Given passengers still have to book the service before walking to the bus stop and waiting (the average wait time is 15 minutes) it’s not clear these services are really any more ‘flexible’ than a regular bus that turns up without you having to call for it in advance.

But it’s the third problem with on-demand service that may be the most fatal, given the way microtransit is advertised to planning agencies as a cheaper alternative to regular bus service. Transport planners now have over 5 years of evidence from microtransit pilots in real-world cities, and it all points to one conclusion: microtransit doesn’t cost less to operate, and actually involves a higher level of subsidy per passenger than a typical low-patronage bus route.

As Angie Schmitt writes in StreetsBlog, many microtransit pilots have failed in practice even when judged by their own criteria.

An early experiment with the now-bankrupt Bridj in Kansas City was a complete flop. Riders made only 1,480 trips during the course of the one-year pilot, even though each passenger got their first 10 rides for free. Only a third of riders kept using the service after the free rides expired. The local transit agency, KCATA, spent $1.5 million to administer the service, for a jaw-dropping subsidy of more than $1,000 per ride.

The Santa Clara Valley Transportation Authority, serving San Jose and its suburbs, began a micro transit experiment in 2015. Again, the results were woeful. The Eno Center on Transportation reports that it generated only 0.4 boardings per hour that a vehicle was in service, a tiny fraction of the 15-boardings-per-hour threshold that VTA requires to keep running bus routes. The core ridership of the micro transit service consisted of just 20 people, according to EnoTrans.

—Angie Schmitt, “The Story of ‘Micro Transit’ is Consistent, Dismal Failure”, StreetsBlog, June 2018

Other microtransit projects claim to be succeeding, as in Sacramento and Austin. But as Schmitt points out, the measure of ‘success’ here is still a paltry 3 passengers per service hour. This level of performance is on par with traditional ‘dial-a-ride’ bus services, as have been provided in North American cities for decades (and which many microtransit pilots are replacing). But it’s still far less than what even a poorly patronised timetabled service achieves.

Since [expansion of the service], SacRT’s micro transit has performed better, averaging 3.24 rides per service hour during May and June. If sustained over a whole year, that’s a 45 percent increase in efficiency over the in-house service, but still well within the typical range for dial-a-ride transit, which maxes out at around six trips per hour. (By comparison, even the least productive bus routes get 10 or 15 trips per service hour.)

Meanwhile, in Austin, Cap Metro reports that its micro transit pilot averaged 3.04 riders per service hour over a full year, topping out at 3.65 in the best month. The pilot served 20,000 trips over the year, or fewer than 55 per day….

It’s fair to say that these micro transit pilots — the best I could identify — were successful as substitutes for dial-a-ride transit. But they do not offer much support for the idea that micro transit is a game-changing innovation.

—Angie Schmitt, “The Most Successful ‘Micro Transit’ Pilots Are Performing Like Decent Dial-a-Ride Services”, StreetsBlog, June 2018

It’s clear subsidies per passenger will always be high when the service carries very few passengers. But because of the inherent low-occupancy nature of microtransit, this high cost base persists regardless of how many passengers are carried overall. That is to say, microtransit lacks the economies of scale inherent in regular public transport. And this is a huge problem, as seen in the outer Toronto suburb of Innisfil where the local government decided to subsidise Uber rides instead of providing a bus service. With this being the only ‘public’ transport option available, and with microtransit lacking economies of scale, the town council has been forced not only to raise the out-of-pocket fare but also to restrict how often people use the service!

“I would never get on a bus in Toronto and hear the driver say, ‘Sorry, but you’ve hit your cap,’” [resident Holly] Hudson said. “Uber was supposed to be our bus.”

—“When a town takes Uber instead of public transport”, CityLab, 29 April 2019

The same story has been playing out in NSW, as planners in Australia experiment with microtransit. As a report on News.com.au states, a trial of Uber-style on-demand buses in several regions of Greater Sydney appeared to be costing up to $180 per passenger carried, and recovering just 3% of operating costs from fares. (Melbourne buses, and Sydney buses outside the inner suburbs, have long performed worse on cost recovery than both trains and Melbourne trams, but even they manage to recover around 20% of costs.) In May 2019 two of the Sydney trials were abandoned for cost reasons.

The Independent Pricing and Regulatory Tribunal has warned that on-demand services “need to be carefully designed to ensure that high-cost, low-patronage fixed-route transport services are not simply replaced by even higher cost on-demand services”….

In work for the regulator, consultancy AECOM has calculated that the fixed costs for a new on-demand service can range from about 150 per cent to 180 per cent of those for a fixed-route service. There are also likely to be extra running costs such as fuel and driver expenses.

—Sydney Morning Herald, 15 May 2019

At such levels of performance it is readily understandable that microtransit, as with ride-hailing services in general, has not shown any sign of being effective in reducing congestion either. The report New Automobility by Schaller Consulting examined the evidence for the effect of ride-hailing on traffic congestion. The evidence confirms that ride-hailing operations share many of the negative effects expected from self-driving cars: they not only add more cars to the road, they also do this more at the expense of public and active transport than at the expense of existing car travel.

ROLE IN URBAN MOBILITY

1) TNCs added billions of miles of driving in the nation’s largest metro areas at the same time that car ownership grew more rapidly than the population….

2) TNCs compete mainly with public transportation, walking and biking, drawing customers from these non-auto modes based on speed of travel, convenience and comfort….

3) TNCs are not generally competitive with personal autos on the core mode-choice drivers of speed, convenience or comfort. TNCs are used instead of personal autos mainly when parking is expensive or difficult to find and to avoid drinking and driving….SHARED RIDES AND TRAFFIC

1) Shared ride services such as UberPOOL, Uber Express POOL and Lyft Shared Rides, while touted as reducing traffic, in fact add mileage to city streets. They do not offset the traffic- clogging impacts of private ride TNC services like UberX and Lyft….PUBLIC POLICY

1) TNCs and microtransit can be valuable extensions of – but not replacements for – fixed route public transit.—The New Automobility: Lyft, Uber and the Future of American Cities, Schaller Consulting, July 2018

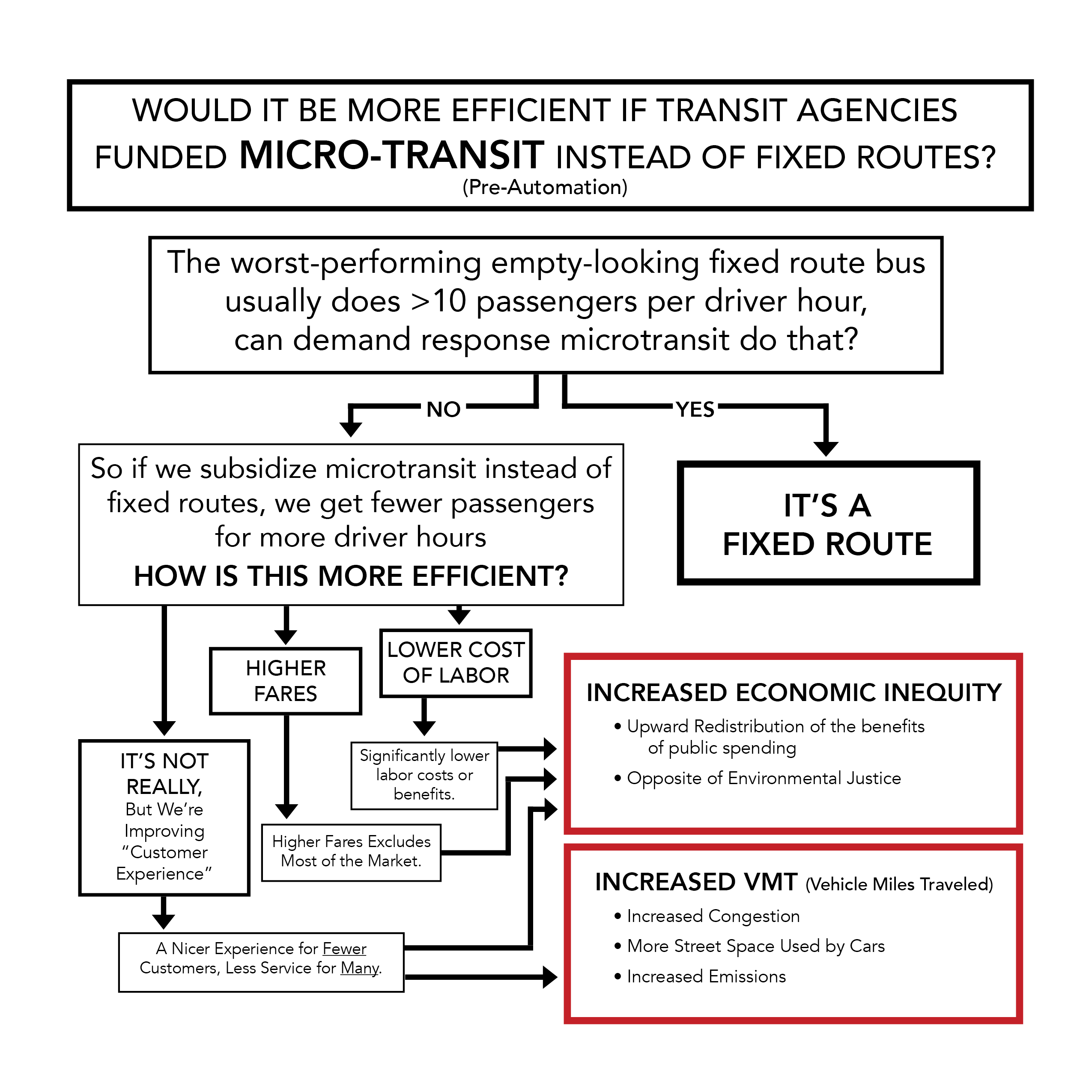

This is all conveniently summed up in the form of a flowchart by US planning consultant Jarrett Walker (from the full article here).

Just what is an ‘underperforming’ bus route?

The Infrastructure Victoria Five Year Focus report gave prominence to its claim that 40 per cent of Melbourne bus routes are “underperforming”. It arrived at this figure by looking at PTV’s line-by-line patronage data for 2016 and applying a performance threshold of 20 boardings per service hour. Routes below this level, it was implied, are likely to be serving areas with low population densities, low job densities, or high car ownership rendering them unviable.

As can be seen above, the ‘boardings per service hour’ metric is useful for assessing public transport services from a day-to-day operational perspective. It provides a handy measure of how effective a service as currently provided is likely to be at raising fare revenue to offset operating costs (the biggest component of which is the driver’s hourly wage). But of course it is purely an observational metric: it does not reveal why a service would be carrying relatively few passengers.

It’s instructive to probe a little more deeply into a few of the specific routes that are “underperforming” by Infrastructure Victoria’s measure. Here are a few that can be gleaned from the route map (Figure 14) in the report:

- Route 232 over the West Gate Bridge to Altona North.

- This is a route that, until a few years ago, was actually quite heavily used by city commuters from the west. But by 2016, this bus was being so heavily delayed between the city and the West Gate (due to a total lack of traffic priority) that it was carrying only a fraction of its previous patronage.

- Route 600 from Sandringham to Southland.

- Back in the 1980s, this was again a highly patronised service. For historical reasons, it was one of very few Melbourne bus routes that formally acted as a ‘feeder’ to trains, with a bus meeting every train and connections built explicitly into the timetable. But in the early 1990s amid other ‘austerity’ cuts to bus services, this feeder function was removed and the route split into three separate routes through Beaumaris, one half-hourly and the others hourly.

It’s only a natural consequence that patronage nose-dived. Indeed, every single public transport service in Beaumaris or Black Rock is considered ‘underperforming’ on Infrastructure Victoria’s criteria, despite the fact these suburbs have demographic and geographic characteristics virtually identical to nearby Cheltenham and Highett where public transport mode share is significantly higher. - Routes in Mill Park, South Morang and Mernda.

- With the sole exception of the 901 SmartBus, not a single bus service in these suburbs meets the 20 boardings per hour criterion. Of course, the distinguishing feature of the 901 is it runs at a higher frequency: the others are without exception every 40 minutes – unattractive to anyone who doesn’t want to live their life according to a bus timetable.

- Route 788 from Frankston to Portsea.

- Users of this route might be surprised to see this as a red line on the map, given it routinely has so many passengers that people are turned away at stops. (And yet it still runs every 40 minutes on weekdays and less than once an hour on weekends!)

What is this route doing on the list at all? This appears to be a quirk of the ‘boardings per hour’ measure, which penalises services for which the majority of passengers are travelling long distances (and hence spending a lot of time on the bus).

Conclusion: Putting buses to work

There is a common factor in the above examples—as well as most of the others on Infrastructure Victoria’s map—that helps explain why they perform relatively poorly despite operating in similar suburbs (in some cases the same suburbs) as other routes with better performance. Factors such as low frequencies, circuitous routes and lack of traffic priority feature prominently in Melbourne bus services, and contrast starkly with Melbourne’s much more well-patronised tram services.

Overall, the higher the route’s frequency of operation, and the more closely it resembles a typical tram route in running direct along straight lines, the more likely it is to fulfil Infrastructure Victoria’s performance criteria. This is the case even though high-frequency routes inherently cost more to operate and have more service hours to fill than low-frequency routes.

‘Demand responsive’ microtransit, meanwhile, might better be called ‘exception based’ public transport. The default is that no service is provided, and explicit passenger action is required to trigger the ‘exceptional’ routing of a vehicle to a particular stop. A public transport service that handles more than exceptional cases gains nothing from operating in this way: only the administrative burden of processing multiple passenger requests for stops that the vehicle will be making anyway. Microtransit makes sense only as a (relatively costly) supplement to a transport system dependent on private cars, not as a mode of transport on which any substantial proportion of the population relies.

As the 2020s progress there are signs the earlier enthusiasm for ‘demand-responsive’ services has cooled, with the Victorian Government introducing fixed-route services in Tarneit to replace FlexiRide services, and delaying earlier plans to introduce FlexiRide buses elsewhere. The poor frequencies of fixed-route buses in these suburbs remain a problem, as they do everywhere in Melbourne, but it’s increasingly apparent that microtransit could never be the silver-bullet solution.

In conclusion, the secret to achieving good performance and cost recovery for bus routes has little to do with embracing the kind of ‘disruptive’ models of service provision that relegate public transport to a residualised mode of last resort. It is more likely to result from the tried-and-true recipe practiced in cities around the world with well-used public transport: high frequencies, full-time service provision and an efficient network with convenient interchange between services. Anything less is likely to continue wasting money relative to passengers carried.

Why have I devoted my career to fixed public transit, rail and bus? Because unlike Musk’s tunnels, or streetcars that are slower than walking, or “Ubering your transit system,” or fantasies of universal microtransit, fixed transit scales. When it’s allowed to succeed, it’s a supremely efficient use of both money and space. Bus service, especially, is cheap enough that you can have a lot of it, everywhere, if you decide you care about liberating lots of people to move around your city. And if you want a city that’s equitable and sustainable remember: if it doesn’t scale, it doesn’t matter.

—US transport consultant Jarrett Walker, “Why write about Elon Musk?“, Human Transit blog, May 2019

Last modified: 22 August 2024